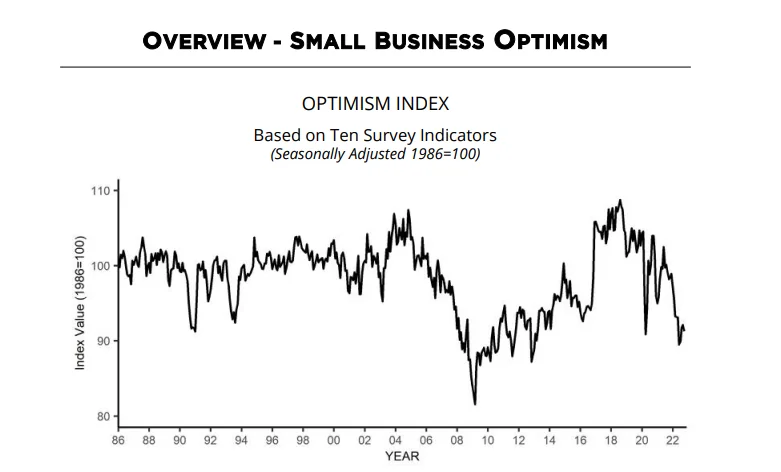

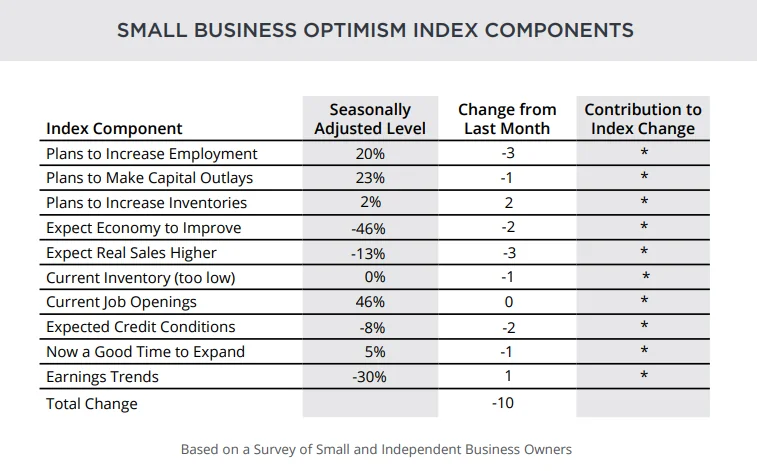

The NFIB said Tuesday that its small-business optimism index fell to 91.3 in October, further below historical average of 98.

The NFIB said Tuesday that its small-business optimism index fell to 91.3 in October, further below historical average of 98. From their commentary: "Success for the Fed is bad news for small businesses, sales will fall, costs will be sticky, so profits will take take a hit. Rough times ahead."

The Optimism Index declined 0.8 points in October to 91.3. This is the tenth consecutive month below the 49-year average of 98. The last time the Index was at or above the average was December 2021. Of the 10 index components, 2 increased, 7 decreased, and 1 was unchanged. Thirty-three percent of owners reported that inflation was their single most important problem in operating their business, 3 points above last month and 4 points lower than July’s highest reading since 1979 Q4. Owners expecting better business conditions over the next six months decreased 2 points from September to a net negative 46 percent. Forty-six percent of owners reported job openings that were hard to fill, unchanged from September. The net percent of owners raising average selling prices decreased 1 point to a net 50 percent seasonally adjusted. The net percent of owners who expect real sales to be higher decreased 3 points from September to a net negative 13 percent.

Real GDP grew in the third quarter by 2.6%. Exports grew significantly, adding 2.8 points to growth (so everything else was slightly negative in total). For the year, with two negative quarters in the first half, the economy is about even, no real growth. Consumer spending has been stubbornly solid thanks to widely held savings deposits and credit. But these sources of spending support will soon lose strength. Then, only job and income growth will keep spending up. Housing has been hard hit by mortgage rates over 7%, starts have tumbled and existing home sales plunged. Rates can rise further as the Federal Reserve continues to raise its policy rate, 75 basis points this month and probably again in December. In the early 1980s, mortgage rates were double-digit, we’re not there, yet.

The frequency of reported price increases was highest in the retail trades, 69%, followed by 64% in wholesale, and 61% in construction. The other industry groups averaged about 50% raising prices, with the exception of professional services at 20%. Clearly, consumers are being confronted with inflation in every aspect of their lives. So far, inflation has been resistant to the impact of higher interest rates. If the Fed were a “fiscal” arm of government, it could just raise taxes on everyone for a short period of time to slow spending. But it can’t and must rely on the tenuous link between interest rates and spending. Major expenditures by consumers can be impacted (cars, houses, boats, etc.), a slow, erratic process. Firms are more directly impacted as the cost of loans (capital) rises, making more and more investment outlays unprofitable and thus impacting employment and income in affected sectors.

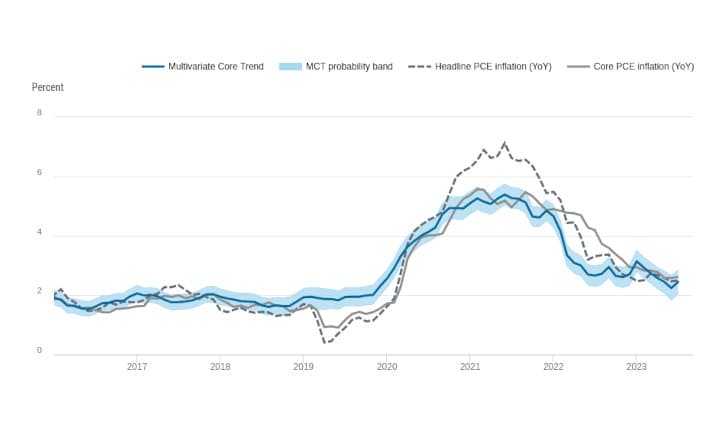

Firms can quickly cut their prices but have little or no control over things like labor compensation or gas prices. The Fed wants inflation to fall to 2%, but that is still inflation. Prices have risen significantly. Will they fall or just stop rising as fast? If they fall, the purchasing power of wage gains will increase for workers. If prices don’t fall, workers have sustained a permanent reduction in their incomes and wealth (savings accounts, 401k values, etc.). It’s the “inflation tax”.

While the Administration keeps pushing for more spending (inflationary) the Fed will persist in doing its best to slow spending (hopefully avoiding a real recession). Success for the Fed is bad news for small businesses, sales will fall, costs will be sticky, so profits will take a hit. Rough times ahead.