Inflation Alert! NOAA is predicting another above-normal Atlantic hurricane season. Forecasters predict a 60% chance of an above-normal season, a 30% chance of a near-normal season, and a 10% chance of a below-normal season + other disasters = $$$

In the continuing series of examing extreme weather from climate change and its impact on the already strained transportation network (1 2 3), I would like to discuss the 2021 hurricane season, which began on June 1st.

National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration (NOAA) is calling fro for a 60% chance of above-normal activity, which includes a range of 13 to 20 named storms--6 to 10 of the storms could become hurricanes, including 3 to 5 major hurricanes (category 3, 4, or 5).

In 2020, there were 30 named storms, of which 14 became hurricanes, including 7 major hurricanes (winds of 111 mph and higher) last year. You may recall the season was so active they ran out of the alphabetical list of names and had to borrow some from the Greek alphabet.

This year, any extra storms will be named through a supplemental names list from the World Meteorological Organization (WMO).

Several factors contributed to NOAA’s prediction for an above-normal hurricane season:

- Predicted warmer-than-average temperatures in the Tropical Atlantic Ocean and the Caribbean Sea

- Weaker tropical Atlantic trade winds

- Enhanced west African monsoon.

The total aggregate cost for the 2020 hurricane season was almost $47 billion (7th costliest). 9 of the 10 costliest Atlantic hurricane seasons have happened since 2004 – the exception being 1992 when Hurricane Andrew caused $27 billion in damages, (all but $302 million of 1992’s costs).

Hurricanes are just another twist up Mother Nature's sleeve that can have an impact on inflation.

2020 marked the tenth consecutive year with eight or more billion-dollar disasters. https://coast.noaa.gov/states/fast-facts/hurricane-costs.html

According to NOAA, there were 13 severe storms, seven tropical cyclones, one drought, and one wildfire event in 2020, which resulted in the deaths of 262 people. Total damages cost $95 billion--the fourth-highest inflation-adjusted annual cost total since 1980, and more than double the 41-year average of $45.7 billion.

https://coast.noaa.gov/data/nationalfacts/img/fast-fact-weather-climate-disasters.jpg

2018 and 2019 each saw 14 billion-dollar weather disasters. Associated losses for 2018 were estimated at $91 billion and for 2019 were $45 billion—for a combined total of $136 billion.

According to NOAA, 2020's 22 $billion+ weather and climate disaster events set a new record from the record of 16 events (up 37.5%) from 2011 and 2017. 2020 was the sixth consecutive year 10 or more billion-dollar disaster events occurred in the U.S.

In the broader context, the total cost of U.S. disasters over the last 5 years (2016-2020) exceeds $600 billion, with a 5-year annual cost average of $121.3 billion. Guess what? both of these are new records!

Damage costs over the last 10-years (2011-2020) were also historically large: at least $890 billion from 135 separate billion-dollar events. Going back further, the losses over the most recent 15 years (2006-2020) are $1.036 trillion from 173 separate billion-dollar disaster events.

https://www.climate.gov/news-features/blogs/beyond-data/2020-us-billion-dollar-weather-and-climate-disasters-historical

As we can see, each region of the country faces its own combinations of recurring hazards. The charts above show how the frequency of disasters differs across both time and space. The combined historical risk of U.S. severe storms and river flooding events makes the spring and summer seasons the high-risk time for simultaneous extreme weather and climate events.

Impacts on transportation we have talked about:

Roads

Higher temperatures can cause the pavement to soften, expand, and buckle. This can create rutting and potholes (especially in high-traffic areas) and can place stress on bridge joints. Heatwaves can also limit construction activities, particularly in areas with high humidity. Due to these changes, it will become more costly to build and maintain roads and highways.

Climate change is projected to concentrate rainfall into more intense storms. Heavy rains result in flooding, which will disrupt traffic and weaken or wash out the soil and culverts that support roads, tunnels, and bridges.

Railways

High temperatures cause rail tracks to expand and buckle. More frequent and severe heat waves or wildfires require track repairs or speed restrictions to avoid derailments. Heavy precipitation and flooding will lead to delays and disruption, and tropical storms and hurricanes can also flood or leave debris on railways, disrupting freight transport.

Shipping

Shipping experiencing sea-level rise will be able to accommodate larger ships, reducing shipping costs. However, higher sea levels will mean lower clearance under waterway bridges. In inland waterways where water levels are expected to decline, as in parts of the Great Lakes, ships could face weight restrictions, as channels become too shallow.

The entire transportation network is already facing spikes in costs and supply/labor shortages, and you can bet any of the severe weather we have discussed above will exacerbate and compound those issues. This will continue to raise costs and those costs will get passed down the line. More fun to look forward to over the coming months. The CPI number from last week is a lie and a joke and this inflation is not transitory--as Covid-19, Suez Canal, and Mother Nature all have continued roles to play in seeing it stick around.

As covered above, I think it is fair to guess 2021 disaster spending will be at least $100 Billion, which will create more demand for goods already in short order in a transportation system likely impacted by the ramifications of said demand.

However, previous demand has about left the cupboard bare of goods available to the economy because the government borrowed and deployed $5 trillion in stimulus over the last 16 months, while the Fed handed out $4 trillion on its own like candy. This caused asset prices to boom while cranking up demand, and obliterating retailer's inventories. The US Census Bureau data from Friday confirms this.

Total inventories at all retailers, from auto dealers to supermarkets, fell to $598 billion in May, seasonally adjusted, down 9.8% from May 2019, the third month in a row of declines, but still up from the low in June last year.

These inventories in May, and retail sales in May, which were down from April, produced the second-lowest inventory-sales ratio in the history of the data going back to 1992, the lowest having been in April...

FYI: inventory-sales ratio (inventories divided by sales) is a metric in the retail industry. A ratio of 1 means that the retailer has enough goods in inventory for one month of sales at the current rate of sales. This would be 30 days’ supply. A ratio of 2 would be 60 days of supply at current sales. The 'healthiness' of this ratio varies from industry (for example 60 days’ supply is considered 'healthy' in the auto industry.

Speaking of the Auto industry:

If 60 days is 'healthy' 30 days is definitely going to lead to the crazy prices we are seeing now...

Inventories at new vehicle dealers, used vehicle dealers, and parts dealers fell to $153 billion in May, down 36% from May 2019, according to data released by the Census Bureau on Friday. And the inventory-sales ratio – with inventories and sales both in dollars, (the impact of inflation gets canceled out), dropped to 1.14, the lowest level in the data going back to 1992...

The ever-more expensive vehicles in inventory over the years explain all of the long-term rise of inventories in the chart above. Sales and inventories with them had huge cyclical swings, up and down, over the past 15 years and went nowhere. In sales, the industry has stagnated and inventories mirrored this. What changed is the prices of vehicles.

As we covered before, there has been an intentional shift in the industry away from lower-margin cars to more expensive SUVs and trucks, which further ballooned the dollars tied up in inventory, without increasing units in inventory. With this in mind, the 36% plunge in $ terms in the total vehicle and parts inventories, from $240 billion in May 2019 to $153 billion in May 2021 is just that much more brutal since prices have run up so much. Yes, semiconductor shortage plays into this in the short and medium-term, but what happens when steel prices won't come back down as lumber has?

https://www.marketwatch.com/investing/future/hrn00

What's going on? During the early months of the 2020 shutdowns, many steel mills shut off production in fear that we were headed into a deep recession—maybe even a depression. But that drop-off in demand didn't last long for iron ore. Early in the pandemic, stuck at home Americans rushed to spruce up their abodes. Soon, steel-heavy products like grills and refrigerators were in high demand. That quick rebound caught steel mills off-guard.

"What happened, which is similar to lumber, demand during COVID-19 was stronger than first anticipated because of switches in consumption patterns. Instead of paying for experiences and vacations, they were buying a new lawnmower, buying a new car, or white goods like appliances—which are steel-intensive," Thorsten Schier, a metals expert at Fastmarkets, tells Fortune.

https://tradingeconomics.com/commodity/lumber

What's driving the price correction in lumber? I believe as lumber prices went bonkers this spring, some homebuilders and DIYers finally started to back off. In May, new home construction (down 8.8%, remember median price jumped to a record $374,400!) and home improvement sales (down 8.1%), from their March highs.

On the supply side, meanwhile, sawmills—incentivized by record-high prices—upped their production levels. That combination of increased supply and weakening demand is helping to alleviate the lumber shortage.

However, unlike lumber, steel is less dependent on DIY or new home construction. In fact, many industries that are steel-heavy, like oil and gas, are seeing demand soar right now as the economy reopens (and the price above reflects). Oil producers and refineries will only need more steel in the coming months as Americans return to air travel and their daily commutes.

"I don't think we've hit the peak for steel prices. Most people in the market see strength through the third quarter, and some don't see it getting better on the buying side until 2022 sometime," Schier says. "It is just that supply is that tight. People are scrambling for material."

Another factor: Consolidation. Two major acquisitions last year by steelmaking titan Cleveland-Cliffs—AK Steel for $1.1 billion and U.S. steel mills from ArcelorMittal for $1.4 billion—has essentially made the steel industry a duopoly. That firm grip by Cleveland-Cliffs and United States Steel Corporation on the market, Schier says, leaves them with little incentive to increase production. After all, creating more supply would only mean their prices would fall.

The other wildcard at play are global supply chains issues. In particular, the chip shortage which is hampering new car production. Once the chip shortage is resolved, the automotive industry is expected to ramp-up. More cars rolling off production lines, means more steel demand.

Fastmarket's Schier was blunt with his short-term steel assessment: "There doesn't appear to be any sign that it is abating anytime soon."

I guess what I am trying to say is car prices are going to stay high while inventory has trouble being cranked up, semiconductors now, steel later...Inventories at food and beverage stores

After the great toilet paper shortage from spring of last year, shelves have recovered overall and edged up to a new record of $54.4 billion in May.

Because sales at these stores were about 15% higher than they’d been before the pandemic, they pushed down the inventory-sales ratio to 0.73, compared to the multi-year average before the pandemic of ~

0.78. Food and beverage stores are increasing their dollar inventory overall, but are turning it even more quickly, which gives rise to sporadic and brief shortages in some items now here and there.

With inventories depleted, trouble likely on the horizon from Mother Nature, how is there any chance of prices going down? This inflation beast in the 'real economy' is insatiable and wants EVERYTHING!! (sidenote, I do think we will see deflation in asset prices when all of this goes down).

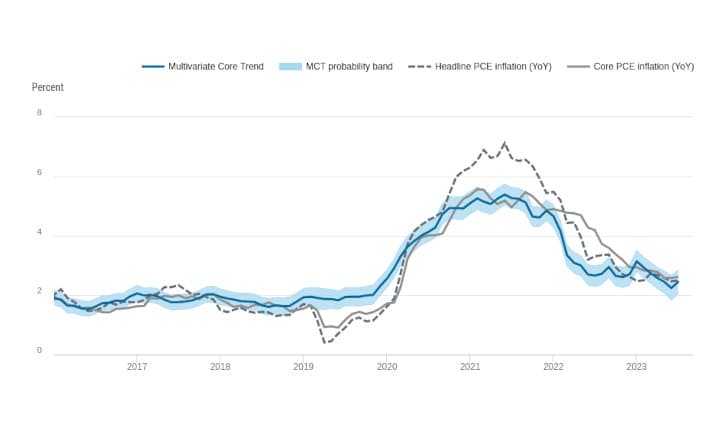

All of this pain in the transportation system happening in the backdrop of the Fed still plowing away with $120 billion in assets purchases each month:

$40 billion a month in mortgage-backed securities. This will continue to depress mortgage rates and only continues to add gasoline to the inflation fire.

$80 billion in Treasury securities a month (with policy rates near 0%): represses short-term and long-term interest rates in general, and inflates asset prices and consumer prices, which further DESTROYS the purchasing power of the dollar.

TL:DR The Dollar losing purchasing power + Inflation = Permanent Loss of purchasing power. This will likely be amplified by the demand created from extreme weather events and the lack of current inventory discussed in detail above.

Buckle Up.